I was reading a few news stories lately and they all seemed

to shed light on an idea I’ve been thinking about a bit lately.

Regular readers will know that I do a reasonable degree of

volunteering, between SES and the Legal Service and the Blood Bank. I’d actually like to do more: if I had the

time at the moment (I don’t) I’d try and set up an active Red Cross unit in the

Goulburn Valley (the one that currently operates in this area is essentially a dozen elderly ladies) with a focus on disaster relief as opposed to disaster

response. The thing is, I don’t think

that any of this volunteering makes me a good person at any level. Volunteering is simply what I do: you don’t

expect to be called a good person for breathing (a line I have admiringly cribbed from

Harper Lee). I don’t think I’m unusual

in this. I suspect that most of

the volunteers I know do it because it’s just what they do.

This was on my mind when I read about a ‘dirty bomb’exercise conducted by the Utah National Guard (and others). The story covered the dangers and hazards

posed by a dirty bomb and the sort of training that disaster responders do to

be able to respond to such things.

Image from here

The story said that -

In a highly regimented, systematic process, four guard members would carefully lift and place each victim on a portable gurney. The crew would gingerly carry the victims onto a conveyer system with metal rollers, laying patients onto solid plastic backboard, where they were manually pushed up through plastic slats into the decontamination room.

Technicians would then spray water through a rubber hose, extensively dousing each victim to remove potential elements of contamination.

Victims would then be gently pushed outside the unit to awaiting Guard members, down the conveyer system. The more seriously injured were taken onto a gurney while others walked, escorted by guard members.

After assessing individual levels of visible trauma, each victim would go to a tent were awaiting medical staff from Sky Ridge and the National Guard who would treat them.

Extensive medical equipment and supplies were ready to treat injuries that ranged from minor cuts and scrapes to severe exposure to a dirty-bomb explosion.

I don’t think any of the responders to an actual such emergency would be comfortable hearing phrases about “being ready to put their

lives on the line”. The people I’ve met

in the SES don’t, I think, see ourselves doing this at all. Sure, we do work that is (for want of a

better adjective) dangerous - getting up on a roof in a rainstorm, for instance

– but we’re trained to do it in a way which is about as dangerous as crossing the

road. I think we’re much happier and

prouder to know that we do technical and challenging work efficiently, skilfully

and with a minimum of fuss.

I think that this is important. I don’t trust words like 'hero' or 'angel'. It's too tempting to believe it, and to believe your organization can do no wrong.

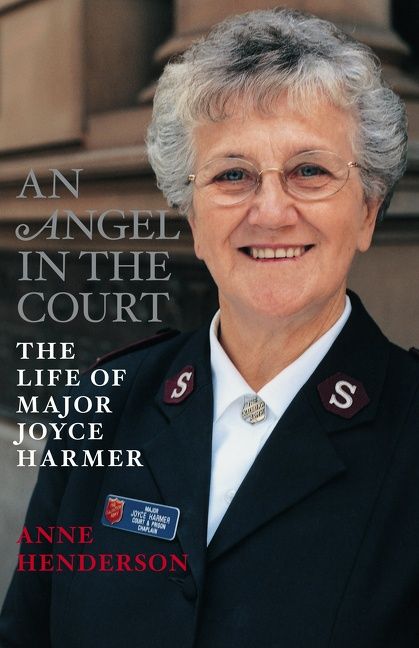

Image from here

My instinct says that this may be how the

Mississippi Red Cross got itself into trouble recently, delivering flood relief

where it was not needed and avoiding areas where they could have done real

good. They were said to be intent on running their own program and not co-operating with local authorities, and to have no desire to change. Disaster response, like emergency response,

is nothing so much as a team effort. All

the teams have to work together.

Image from here

I think the strength of the SES especially is that its

members seem temperamentally unheroic. Looking

around the people I know, there seems to be a common profile. Our occupations are respectable but not

glamourous: cabinet makers; gardeners; auto electricians; minor government officers; retail assistants; cooks. We

often swear like troopers. More than a few have messy personal lives. Our overalls are usually grimy and our boots

are never polished. Not heroes, not

angels, and not glorious. We just show up when things turn to shit.

I can’t think of people I’m happier to work with.

No comments:

Post a Comment