The general idea

The first conflict which I think we can confidently say was part of the creation of the Pax Atlantica were the United States' First and Second Barbary Wars. I will be intrigued to read Brian Kilmeade's recent book on the subject, but the essential idea is straightforward: The north African Barbary states had a policy of tolerating and encouraging acts of piracy and ransom against European and American shipping. This became intolerable to the recently independent American states, which in two wars dispatched (among others) the warship USS Philadelphia to assert freedom of navigation in that region.

As I mentioned in the thought-bubble, in between the Barbary Wars Britain established the West Africa Squadron with the objective of abolishing the African slave trade. In effect, an entire area of commerce which involved a particularly arbitrary type of imprisonment and cruelty was suppressed. Slavery itself would not be abolished in the British Empire for another twenty-five years. However, some idea of the importance attached to the mission can be had from the deployment to the West African fleet of a fast, modern warship like HMS Hydra.

HMS Hecate, a Hydra-class vesselImage from here

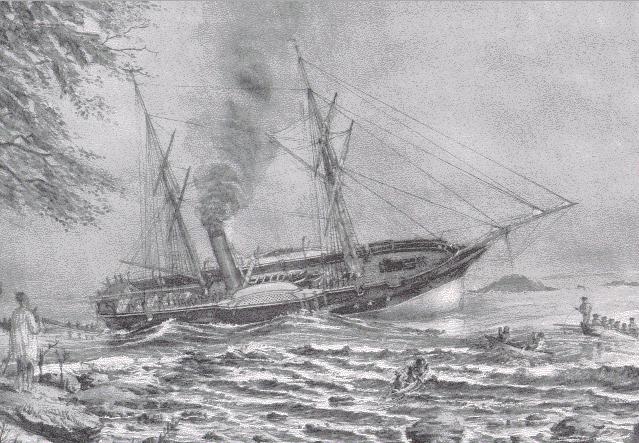

The same idea can be seen at work in the Opium War between Britain and China of 1839-1842. In today's world, it would be hard to argue with a straight face that British hands - seeking to sell drugs into China - were clean. On the other hand, the seizure by Chinese officials of over 1200 tons of opium without compensation was at least at the boundaries of legality. In this light, the war for improved rights of trade and commerce reflected a legal order that was already becoming received wisdom.

When everybody was right

With its combination of good reasons and dirty hands on both sides, the Opium War was a kind of prelude to the much larger tragedy of the American Civil War where both sides could claim to be upholding the rule of law. We don't need to get into the ancient debate over whether slavery was the sole cause of the war (1): it's sufficient for the present discussion that one accepts it was at least a relevant factor. What's important is that Southern slaveholders could legitimately claim that slavery was sanctioned by law and the use of force by the north to abolish slavery broke that law (2). The converse was also true. The Union could make a non-absurd argument that secession was simply unlawful (3). I have seen one contemporary document that described the conflict as "the war for the union". For better or worse, both sides sought to uphold the rule of law, manifested in the property and labour law and constitutional law.

Long shadows

This trend reached its summit in 1914, at the end of the long nineteenth century. For the British Empire at least, the First World War was a conflict for the rule of law. The United Kingdom's stated reason for entering the war was the defence of Belgian neutrality: in 1839 Germany signed the Treaty of London creating the Kingdom of Belgium, with that Kingdom recognised as remaining a neutral power. It was that promise of neutrality which the German Empire intended to violate by executing the Schlieffen Plan in order to inflict a rapid defeat on France. Britain's acceptance of this as a cause for war declared that it was willing to shed blood to maintain the rule of international law. Its willingness to endure horrendous bloodshed in this cause was a demonstration that the rule would not be violated with impunity.

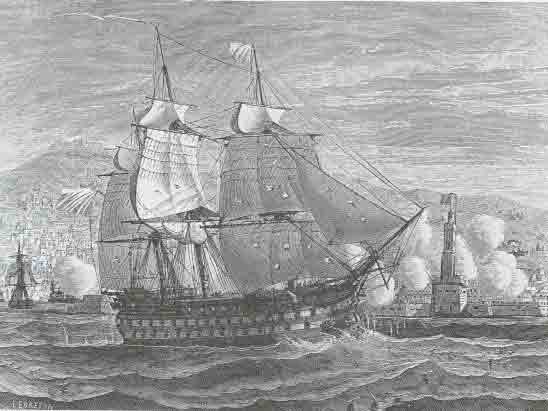

Perhaps one reason the Great War seems so meaningless today is because the rule of law between nations is more-or-less taken for granted: the sovereign power of making war that President Hussein sought to exercise with the annexation of Kuwait in 1990 the Persian Gulf War. A long-running dispute between Nicaragua and Costa Rica over the location of their border has lead not to a call to arms or a gallant defence of the Fatherland, but to proceedings in the International Court of Justice. And the 'addled' wars of the nineteenth century are not easy to imagine, or justify. The War of 1812, for instance, stemmed from Britain's assertion that American seamen could be impressed into the Royal Navy, and the Unites State's assertion a right of conquest over Canada. France's conquest of Algeria, too, resulted less from policy and more from poor diplomacy and poor decisions on all sides.

Hercule - French flagship in the conquest of AlgeriaImage from here

I don't think any writer who wanted to be taken seriously could regard the period between 1789 and 1914 with unqualified admiration, at least as far as the diplomacy and war-making was concerned. As ever, there were mixed motives, cruelty, vanity and greed. But the idea that even nations and sovereigns are bound by laws, and that those laws will be upheld, lay at the heart of the Pax Atlantica.

========================

(1) Interestingly, even impeccably conservative historians consider that the war was fundamentally about the preservation (or otherwise) of slavery: L. Schweikart and M. Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States (2004) at 294.

(2) Id. at 289; Arthur Rizer, ‘Abraham Lincoln: Slavery Hunter’ (2015) 19(2) The Young Lawyer 17.

(3) The argument is set out in the post-war judgment of Texas v White, 74 US 700 (1869).

-

-

No comments:

Post a Comment