I suggest that where flags and the like are concerned, we've been asking the wrong question for a long time. Debates about flags are always about the meanings they express. These meanings don't change; they just build up in deeper layers.

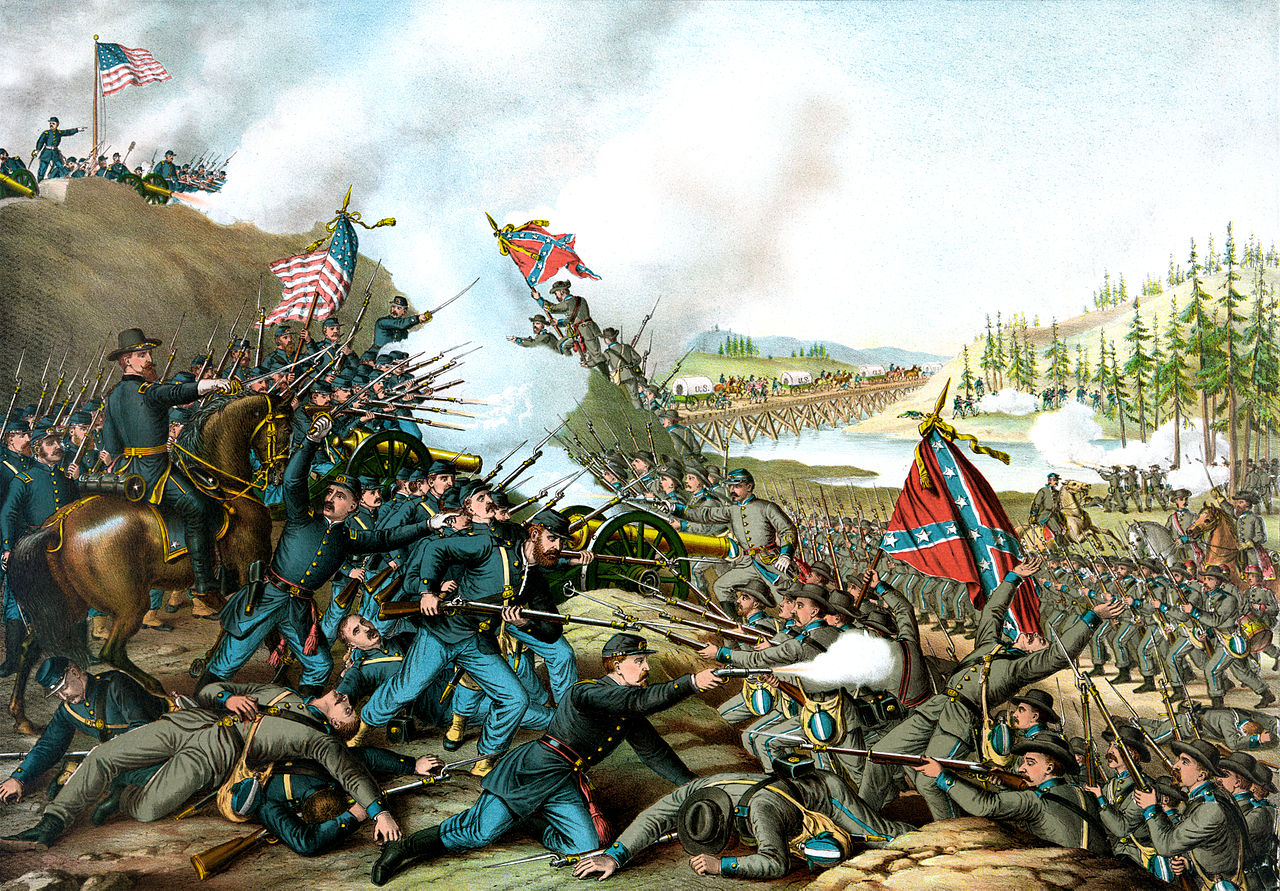

The Confederate battle flag is the best example imaginable. Probably the first meaning to be attached to it was one of tragic valour and regional pride.

Image from here

That meaning still attaches to it: consider its use by the defunct Southern Party.

Image from here

In the meantime it acquired other meanings too. One was the entirely positive quality of independence, irreverence and spiritedness.

Image from here

The other was the negative meaning of violence and bigotry.

Image from here

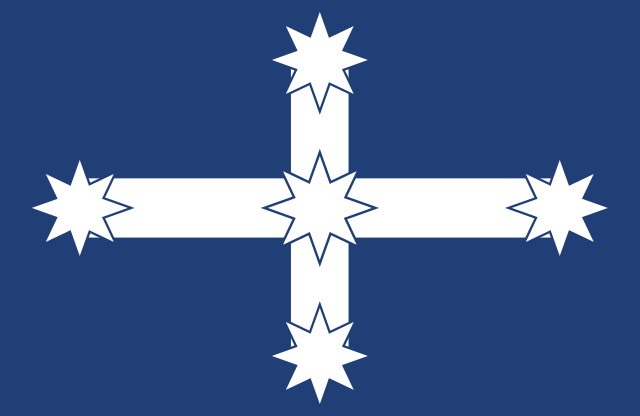

The same fate met the Eureka Flag, flown at the 1854 miners' rebellion at Ballarat.

Image from here

Since then, it found itself adopted both by the hard left of politics AND the hard right, with all the sets of ideas that go with them.

This accreting of meanings means that every flag comes with unfair whispers. An African-American in South Carolina might know that his white neighbour flies the Confederate flag as an expression of pride in his region and his heritage, but it would take a bigger man than most of us to completely ignore the whispering hateful voice that goes with it, because of the extra meanings it carries. The unfairness works both ways: the same white neighbour who wants to show respect for his ancestor who owned no slaves and served in the Army of Northern Virginia will find himself unfairly facing the derision and contempt of people who assume he's a knuckle-dragging bigot.

May I suggest that a way out can be had from the language of heraldry? By adding (or, sometimes, taking away) from flags, their meaning can be made clear. A Eureka flag, for example, that included an image of a tree would refer to ordered liberty and justice* that is far removed from the lawlessness of the Builders' Labourers Federation. A Confederate flag incorporating an open lock or broken chains would convey rebelliousness and independence, and a design that included a noose or a burning cross would convey ... well, something very different.

I know that there is an element of disrespect to the ancestors in this idea, and a degree of meddling with heritage. Certainly it is open to abuse. But perhaps this is a risk worth taking if it means those of us who are living can transmit to those who are not yet born the best ideas of those who are now in their graves.

==========================

* Simon Schama talks about forests having this meaning in Landscape and Memory.

No comments:

Post a Comment